“非遗”档案:永康鼓词

永康鼓词是浙江省永康市独特的民间说唱艺术形式,是以口口相传的形式传下来的。它源于宋代南下的曲子词,到了明代融合而成,清代广为流传。永康鼓词主要是用永康方言表演的,一人多角讲述历史和民间人物故事,在当地一直比较流行。除了永康本市之外,主要分布在磐安,武义,缙云等地区。由于演唱者多为后天性失明男性,所以又称“瞽词”。也因为唱词内容多为除暴安良、伸张正义、男女情爱、乐善好施等,又被称作“唱故事”、“唱公事”或“劝世文”等。盲艺人身着长衫,手握先锋棒,肩背插马袋,常年走街串户,靠唱鼓词谋生。其唱调分为悲调、怒调、喜调、对话叙事和叙情的水平调四种基本调,也俗称作公式调。演唱时,表情丰富,抑扬顿挫,有张有弛;鼓点节奏时快时慢,清澈动听,穿透力强,生动传情。2011年,它被选入第三批国家级非物质文化遗产名录。

The Intangible Cultural Heritage Archives: Yongkang Guci

Yongkang Guci is a unique form of folk art in Yongkang County, Zhejiang Province and is passed down from mouth to mouth. Yongkang Guci can be traced back to Quzici in the Southern Song Dynasty, gaining its wide popularity in the Qing Dynasty after integration with other forms of folk arts in the Ming Dynasty. It mainly adopts Yongkang dialect to tell stories with one person playing several roles. Stories are usually about history and historical figures. Yongkang Guci is mainly spread in such areas as Panan, Wuyi, and Jinyun, and others in addition to Yongkang County. Because most of its actors are blind males, it is called “Guci”, meaning the lyrics of the blind. Most of the lyrics tell traditional stories about peacekeeping, love, justice, the practice of charity and so on. It is also known as “Story-singing”, “Public Affairs-singing” or “Exhortation-singing”. Wearing long gowns, holding a Xianfeng stick, and shouldering a bag, actors would walk from door to door to earn their living by singing Guci all year round, Yongkang Guci has four basic tunes, known as formulaic melodies, namely “flat”, “happy”, “angry” and“sad”. Yongkang Guci has instinctual features of performance. The singing is vivid and expressive with alternating tension and relaxation while its music from drum-beating is clear and rhythmic with alternate slowbeating and fastbeating. It was listed in the Third Catalogue of the National Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2011.

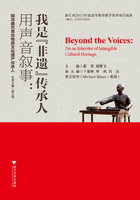

卢顶风:做个唱故事的人Lu Dingfeng: A Lifetime Story-singer

卢顶风,男,浙江永康芝英镇西卢村人。2011年,他被命名为市级非物质文化遗产传承人,代表项目为永康鼓词,以演唱永康鼓词时声音洪亮、高亢而闻名。他是永康曲艺协会现任会长。卢顶风3岁失明,13岁开始拜师学艺,14岁开始自己表演谋生。从2013年起,受永康市“非遗”中心之邀开始在永康二中授课,并定期在永康各地开设免费的成人培训班。

Lu Dingfeng comes from Xilu Village, Zhi Ying Town, Yongkang County, Zhejiang Province. He is famous for his clear and resonant voice in singing Yongkang Guci and was declared among the representative inheritors of Yongkang Guci at the city level in 2011. Now he is president of the Yongkang Folk Art Association. He lost his sight at the age of three and began to learn Yongkang Guci when he was thirteen, and a year later, he started his professional performing career. In 2013, he was invited by the Municipal Intangible Cultural Heritage Center to teach folk art class in the No. 2 Middle School of Yongkang. In addition, he has been invited to deliver complimentary training courses for adults of different towns around Yongkang County at regular intervals.

做个“唱故事”的人

一本鼓词一口田

我三岁时由于发高烧眼睛失明了,所以十三岁那年就去拜徐友为师,学习唱鼓词。我们行内规定拜师学艺年限为三年,但我只花九个月就学成了。我师傅徐友在当时也是比较有名的鼓词先生,对我要求也是比较严格的。师傅首先教我的是一些基本功,也就是敲鼓和打板。一开始我觉得打板很难,节奏很不容易掌控,也摸不到鼓的脾气。师傅把一些要点慢慢教给我,因为教快了是学不会的。师傅也说学这门技艺是要讲究门路的,所以大部分时间都是靠自己慢慢练习。学完敲鼓和打板之后,师傅开始教我唱腔和唱词。唱词是从滩头开始学,然后是诗词,最后是小说故事。当时师傅教我唱的大多是时事新闻为主,我自己学成后出来唱,发现听众不太喜欢听这一类题材的曲目,反而比较喜欢听一些古典小说故事。我当时学的有一套公式调,就是根据场合而分的四种唱调:喜调、悲调、怒调、对话叙事和叙情的水平调四种基本调。至于唱词内容可以根据自己理解编进去,不是死的。唱词人可以根据场合自己随意地编词来唱,去迎合当时的场合气氛。于是我就去买一些古典小说回来,让身边的朋友给我念,我就把故事地点、发生的时间和人物名字记下来,然后自己出去表演唱给听众。效果也是很不错的。所以说,学鼓词的人大多需要有很强的记忆能力。当时我唱的很多故事是由小说改编而成的,像《九美图》、《六美图》、和《朱砂痣》等,其中《朱砂痣》就改编自《薛刚反唐》,讲的是李治和武则天的故事。

以前鼓词在农村是人们主要的娱乐方式,那个时候还没有电视这些东西。白天大家都比较忙,所以我一般出去表演都是在晚上。唱鼓词的场合也不受限制,有时候在祠堂,有时候在茶馆,有时候则是在人家家里唱,一般最早结束也要到晚上十一二点。有时候故事比较长,一唱要好几天甚至半个月,我就在当地村民家吃住,第二天晚上继续演唱。我也比较喜欢唱这种大剧本,主要是因为自己眼睛不方便,这样的话可以少走动。那个时候,晚上唱一场会有一块多的收入,三块为最多。这些收入基本上可以勉强养家糊口,所以当时出现了“一本鼓词一口田”的说法。

卢顶风故事唱词选本《薛刚反唐》

魂牵梦萦鼓且歌

大概在1952年,我们永康自发地组建了一个永康(县)曲艺协会。当时,唱鼓词的有两百多人,后来剩下的只有十五六个人。再后来,在“文革”时期,特别是1966、1967、1968这几年都不让唱鼓词的,像鼓啊这些器具都是要被没收的。我想自食其力,于是学了一点算命的“本事”,开始四处算命为生。1975年的时候我娶了老婆,后来育有一双儿女。到了1977年,我又可以唱鼓词了,心里是十分高兴的,发现自己学成之后就一直非常喜欢唱鼓词。这么长时间没有唱鼓词,感觉自己快憋坏了。虽然刚重新开始唱时觉得有些生疏,但是,行情还是蛮好的。

大概到了1983、1984年,电视开始出现,听鼓词的人就少了。到了1986年,鼓词市场开始萎缩,鼓词发展就更加困难了。到了20世纪90年代,鼓词就更加没有市场了。到了现在,已经很少有年轻人对鼓词感兴趣了。大家都忙着赚钱,哪有时间来听你在这儿唱鼓词!再说现在电视电脑很流行,比鼓词有趣多了。现在听鼓词的人一般都是年纪比较大的人。50岁以上的人小时候都是听过鼓词的,60岁以上的这一辈人是认认真真感受过鼓词的人。所以永康鼓词新一代的传承与发展都是很成问题的。

永康鼓词表演乐器牛皮鼓、竹板和鼓签

竹板敲起亮堂堂

最近几年,国家开始重视非物质文化遗产的保护工作,特别是曲艺这块内容。在我55、56岁那两年开始有补贴。后来在2013年,我们市里非物质文化遗产中心邀请我给镇里的培训班上课。培训班地点设置在永康各个镇上,课程是十天一期。每期课的地点都不同,都是他们安排好,然后派人接送我,因为我眼睛看不见,出行也不方便。

培训班学员女性居多,都是30至50岁的年纪。学员们很多也只是小时候听到过鼓词,没有任何基础,所以我教他们也都是从基本的敲鼓和打板开始,然后是滩头和一些诗词。像打鼓和敲竹板,我也只是把要点说一下,然后叫大家自己回家练习。唱词这些的话,一般都是我先唱,他们把词一句句写下来。然后是我唱一句,他们跟一句。上课时间比较珍贵,好在他们学习的劲头很足,学起来也很认真。我现在在培训班上课教的滩头是比较简单也很通用的,有一段唱词意于戏谑杭州的大姑娘,为了给听众制造出笑点,用词是比较夸张的,唱词内容是:

竹板敲起亮堂堂

要唱杭州的大姑娘

裁缝尺背着量一量

量一量三十六丈长

杭州城头当凳坐

钱塘江来当浴堂

一天洗得三次澡

虾兵蟹将都毒光

……

但是如果说要教唱故事的话,就比较不现实。一方面是由于学员们基础还不是很扎实,俗话说做事情要一步一个脚印嘛。还有一个原因就是故事太长比较难记住,大家学起来也比较吃力,而且会打击学生学习的劲头。

另外,文化馆的相关人员还安排我每个星期去永康二中上课,到目前为止已经上了三年课了。在我之前,也有一个先生在那里上过课。现在很多孩子也开始会唱了,我心里也很高兴。在永康二中上课的话,学生一般兴趣不大,但是也偶尔会有几个孩子,学得比较认真。而且都是永康人,唱词也大部分能懂。可惜我不会说普通话,所以要出去表演的话,沟通交流就不是很方便。我怕我唱的他们听不懂。如果我会说普通话,我还想去大学里表演,让大学生们也来听我唱鼓词。有机会我还想去大学里教唱永康鼓词呢!

对于永康鼓词来说,结合现在的时代特点,我觉得要真的把它一直唱下去的可能性不太大,因为市场本身就已经不足了。再加上我们这个年纪真正会唱鼓词的人数也在不断减少,我个人觉得应该把它保护起来,不要让这一文化从此就消失了,没有留下任何痕迹。在很久以后,当人们提起永康鼓词的时候,我们要拿得出证据来证明这一东西以前确实是有的。以现在的状况来说,不能一直纯正地传唱下去,已经是很遗憾的一件事情了。如果连保护也成为问题,那么真的就是让人痛心了,毕竟它曾经是很受欢迎的一门艺术。所以我觉得我们现在要以保护为主,传承这一方面可以稍微放松一点。最好的话两样都不落下。

卢顶风演唱和教学图片

A Lifetime Story-singer

To Be a Guci Singer Means to Be a Bread Winner

I lost my sight at the age of three as a result of a high fever, so I became a disciple of Master Xu You to learn Guci for a living at the age of thirteen. At that time, it was a rule of practice that all disciples should learn from their master for at least three years. However, I just spent nine months altogether to finish my apprenticeship. My master Xu You was quite famous at that time for Guci singing, and he was very strict with me. First, he gave me some basic training on beating drum and using clappers. In the beginning, I was confused about using clappers, and I thought it was quite difficult for me to control them. My master taught me the basic tricks step by step, or it would be out of the question for my further study. Master Xu also said that Guci learning called for patience, and I should practice more if I was determined to master it. So most of the time, I was practicing on my own. After the successful completion of the first step, Master Xu started to teach me arias and librettos. In terms of librettos, I was taught short poems in the beginning, then the long poems, and then the long folk stories. He primarily taught me to sing news of current affairs, but when I finished my apprenticeship to start my performance, I found that people seemed not to be interested in listening to these subjects. On the contrary, they showed more interest in historical stories and folklore. By then I had learned the tunes of Yongkang Guci that are a set of formulaic melodies and has four basic turns, namely “flat”, “happy”, “angry” and“sad” which meant I could apply them flexibly in accordance with the situational contexts. Since the librettos were not fixed, I could change them in line with the atmosphere in various circumstances. Thus, I bought some classical Chinese novels and asked my friends to read them to me. Then I tried hard to remember them on the basis of the heroes, the time and place of the story so that I could perform to my audience. My efforts brought me a good response. Generally speaking, people who learn to sing Guci have to have a good memory. Most stories I sang in my early performances were adapted from historical novels, such as Portraits of Six Beauties, Portraits of Nine Beauties and Zhushazhi.Zhushazhi was adapted from Xue Gang Rebels against the Tang Dynasty.It is about the love story between the Emperor Li Zhi and the Queen Wu Zetian, the only Empress of China.

Yongkang Guci used to be one of the major forms of entertainments in the countryside during the time before television came into our life. People were busy with their work during the day and had no spare time to enjoy our performances. So Guci singers usually performed in the evening. There was no regular place for the performance, sometimes in the local ancestral hall, sometimes in a teahouse, and sometimes even at someone's home. The performance would not end until midnight or even later. Usually, a whole story would last for several nights or half a month. If so, I would put up at some local people's home so that I could continue my performance the next day. Personally, I like singing long stories in one place because that could avoid the trouble of moving around, as it's inconvenient for a blind man. At that time, I would get one yuan or so as a reward, after one night's singing. If lucky enough, I would get three yuan. Thus, I could almost support my family by singing Guci. So a saying was widely spread among the masses in my hometown:“A Guci singer is a bread winner.”

Obsession with Guci Singing

It was about in 1952 that artists in Yongkang all agreed to create the Yongkang Ballad Singers Association. There used to be two hundred members of whom about fifteen are still alive today. During the “Cultural Revolution” (1966—1976), singing Guci was not allowed, especially from 1966 to 1968, and drums and clappers were impounded. I wanted to make my living with my own ability, so I learned to be a fortune teller to get through those days. I married my wife in 1975, and later we had a son and a daughter. In 1977, I could start singing Guci again. I found myself seriously addicted to my profession as a story-singer. I could hardly bear life without singing Guci for such a long time. Though I felt somewhat unfamiliar when I restarted my singing, my performance was still popular among the audience.

It was around 1983 or 1984 when televisions came into our life; people were not so interested in Guci anymore. In 1986, the market of Guci was shrinking, causing great difficulty to its survival. By the late 1990s, Guci was on the verge of extinction. And now, there are few young people showing their interest in it. People are busy with earning money, having no time and no desire to enjoy it. What is worse, television and computers give people much more distraction than Guci. People who would like to enjoy it are mostly the senior citizens; those who are over fifty have childhood memory of it, and those who are over sixty have their affection for it. Yongkang Guci is faced with the problem of lack of successors, and it has great difficulty for further development.

Clappers' Crispy Sound Lit the Room Up

In recent years, our country has started to pay attention to the protection of our intangible cultural heritage and especially to the protection of folk art. And I started to get subsidies from the government when I was in my middle fifties. In 2013, the local Intangible Cultural Heritage Center invited me to give ten-day free training courses for adults of different towns around Yongkang County at regular intervals. Arranged by the Center, lessons were given in different places. Considering my old age and disability, they would drive me to class and drive me back.

Students in classes were generally women from thirty to fifty years old. They had no basics of Guci singing and had heard it when they were just little kids. So I taught them from the very beginning as I had ever experienced: drumbeats and clappers, then short poems and so on. Customarily, I told them key points and let them practice by themselves. In class, I sang the lyrics to them first, and they would write them down line by line. After that, I taught them to sing the words sentence by sentence. My students were quite diligent in study, and they cherished their class time a lot. What I taught in class was quite easy and basic. There was one passage teasing a young lady from Hangzhou, in order to provide the punchline for the audience, the lyrics were much exaggerated. The script is as follows:

Clappers' crispy sound lit the room up

Sing something about the lady of big size from Hangzhou

Shouldering a tailor's ruler to measure her

Measuring her height out: 400 feet

She takes the top of the city wall as a stool to sit

Takes the Qiantang River as her bathroom

Taking a shower three times a day

The aquatic creatures in the River were poisoned away

…

If I expected my students to sing long narrative poems or fictional stories, it would be unpractical. On the one hand, they did not have a command of the basic skills. Just as the old saying goes: Don't try to run before you can walk. On the other hand,such long poems and stories would trouble them a lot. Because of their ages, it was a big challenge for their memory. Moreover, the students' interest would decline rapidly.

In addition, our local cultural center arranged for me to give classes in Yongkang No.2 Middle School every week. This activity has lasted for three years. There was another artist teaching there before. Some children picked up Guci then, and I was very glad about that. Actually, there are few children showing interest or desire for it, but several among them would learn it seriously. We are all from Yongkang, so there is no big problem for them to understand the language. It is a great shame that I cannot speak Mandarin which limits my chances of going out to perform. Yongkang dialect is beyond the comprehension of outlanders. And I am afraid that people cannot understand what I sing or perform. If I could speak Mandarin, I would like to perform in college to show college students what Yongkang Guci is like. Situation permitting, I will be pleased to teach it in universities and colleges.

Taking the characteristics of the current times into consideration, I think there is little possibility to carry on Yongkang Guci as the market is shrinking. Another reason is that some artists passed away; the urgent task is to protect the art in case it will become extinct with the death of those old artists, leaving nothing to later generations. I hope that when people mention Yongkang Guci far in the future, we are able to come up with the evidence that it did exist in Yongkang. It will be a great pity for all of us if no adequate consideration is given to its protection. After all, it was once a popular folk art. In my opinion, we should take protection as the first step then inheritance. Nothing can be better if both can be achieved.

当青年人遇到鼓词

在偶然间遇见鼓词

说来惭愧,作为英语专业的学生,我很少有机会接触一些传统文化知识。我也从未想过有一天我会接触到曲艺文化,更别说是永康鼓词。从开始搜集有关永康鼓词的资料起,我的人生词典里出现了很多以前一直缺位的词语:非物质文化遗产、曲艺、“非遗”传承人……随着对这些词汇的认识,一些原本缺失的知识得以弥补,我的世界里多了一些别样的色彩,生命里也就此烙上了鼓词的印记,而这一切都源于一次对永康鼓词传承人卢顶风老先生的访谈。

卢老先生在很小的时候,因为一场发烧而失明。十三岁的他为了谋生,开始学习鼓词。没想到,这一唱就是一辈子。因为有天分,他掌握得比别人快,很快就出师了。以前,农村里的村民都还是很喜欢听鼓词的,卢老也就乐此不疲地唱鼓词。长故事唱个十天半个月也是很正常的。后来“文革”犹如一场暴风雨,使得卢老先生和鼓词饱受摧残。这期间,卢老先生为了生存,学会一点算命,也结婚生子。“文革”结束后,因为热爱,他重新回到鼓词的怀抱。但是,20世纪90年代随着电视的兴起,鼓词也逐渐落寞。到了21世纪,鼓词几乎没了市场,而老先生对鼓词就像对待自己的孩子一样,依然不离不弃。

直到最近几年,鼓词作为非物质文化遗产受到国家和社会的重视,老先生也并没有因此而浮夸,始终默默地、不卑不亢地唱着他的鼓词。不因鼓词带给自己苦难而放弃,也不因为鼓词带给自己荣耀而骄纵。一生被烙上鼓词的印记,不以物喜,不以物悲,始终如一。正是卢老先生身上的鼓词印记给我以及我的小伙伴们带来了一种无以言表的冲击。

当鼓词面对现实

永康鼓词,作为浙江省金华地区的一种重要的曲艺形式,以其独特的表演方式和那婉转悠扬的曲调和唱词,伸张正义,劝诫世人从善,树立好的道德品质。清脆的鼓声一敲响,竹板一打,加上独有的永康方言,流传几千年的中国韵味就出来了。从古至今,永康鼓词经历了无数个朝代,见证了历史,成为文化的记忆和弥足珍贵的珍宝。然而,如今永康鼓词也随着卢老师这一代鼓词艺人年岁的增大而面临着传承的困境。

随着时代的进步,人们的娱乐方式不断丰富,花样也越来越多。快节奏的生活在不断地剥夺我们静下心来听鼓词等这些曲艺的时间和心情。这些古老的文化在不断地褪色,有的即将消失在历史这个舞台之上。现如今很少有年轻人对这些东西感兴趣。永康鼓词现在后继人才极度缺乏,永康市文化部门采取了有效措施:比如,加大宣传力度,使永康鼓词变得家喻户晓;邀请鼓词艺人到各个镇里或者中学开设培训班等,有意识地培养鼓词后继人才。

历史之河浩浩汤汤,谁也阻挡不了时代的步伐。我是比较赞同卢老先生的观点的:我们应该采取有效措施,竭尽全力地保护鼓词。哪怕我们无法让它一直传承下去,我们至少要努力让它保存下来。没有谁可以承担让永康鼓词这样的非物质文化遗产在我们这一代消失的责任。有过这次的经历,总觉得自己懂了很多,面对现实,又总萦绕着莫名的隐忧……我觉得我们作为新一代的年轻人有责任让更多的人意识到这一曲艺形式的存在,意识到文化强大而无形的力量。

当非物质遇到物质

“非物质”在英文中是intangible,意为“无形的,无法触摸的”。非物质文化在定义上指那些无形的文化形式,包括艺术表演、社会民俗、节庆、手工艺等传统习俗和艺术。非物质文化的保护和传承其实在某种意义上是坚守着中国一份特有的韵味和格调,而这一点在追求物质文化风气盛行的当下中国尤为重要。

庆幸的是,今天的中国仍有人就像麦田里的守望者一般守卫着我们的文化,我们采访的卢顶风老人就是这些人中的一员。卢老是永康市级非物质文化遗产永康鼓词的传承人,他在用一生演绎这一独特的曲艺形式,诠释历史悠久的中国韵味,但是一个人的能力毕竟有限。所以我们大家都应该竭尽所能地拾起这份中国韵味,保持这份中国格调,让非物质成为物质生活的一部分,让传统成为现代生活的一部分,让古老文化成为时尚文化的一部分。永康鼓词可以成为生活的一部分。在清幽的公园里,清早或者晚上,年轻人和老年人漫步其间,空气里响起永康鼓词的唱段,那该是多么美好的画面。

要让鼓词成为生活的一部分,我们还要思考一些更为现实的问题。由于永康鼓词是用方言传唱的,虽然很有地方特色,但是这也成为永康鼓词的一个局限,导致它很难发展。不懂永康方言的人也就听不懂在唱什么,更没有耐心来听。所以我个人觉得可以以普通话的形式来演唱,曲调和唱腔都保持原汁原味。这样一来,市场范围扩大。甚至可以挑选一些经典的唱段改编为英语,向世界介绍这种独特的曲艺。永康鼓词多是口口相传下来的,如今永康鼓词现存的唱本少之又少,虽然一些传承人的唱段都有被录制保存下来,如果后人要学,单单根据音频也很难学唱。所以,很有必要把永康鼓词的一些著名唱段唱词以文字形式记载下来。同时我们应该考虑一下唱词的改编,当然也要遵循其原本的一些特色、技巧,从而能使永康鼓词总体上紧随时代的步伐,迎合当今大众的口味。

若要使非物质文化的传承成为时尚,成为精神生活必不可缺的一部分,我们需要卢顶风这样的守望者,也需要在非物质文化中注入新的时代气息,这是包括传承人、政府、社会、文化学者甚至是我们大学生在内的所有人的一份责任。

参访人员与卢顶风的合照(左数第二个是当地好心村民,翻译人员)

When the Young Come across Guci

My Accidental Meeting with Guci

As students majoring in English, it is a pity that we scarcely have the opportunity to be acquainted with our traditional culture, and I never imagined that I could get the chance someday to know folk art, let alone Yongkang Guci. Such words as “intangible cultural heritage”, “folk art”, “inheritors of intangible cultural heritage”, and others were not in my consciousness before I was able to collect data about Yongkang Guci. Meeting these words made up for the lack of my knowledge in this field and enriched my life with the mark of Guci, all of which started with the interview with the inheritor of Yongkang Guci, Lu Dingfeng.

When Lu was very young, he lost his sight as a result of high fever. So he set about learning Guci to earn his living but never expected to be a lifetime singer. With his talent for art, he mastered singing faster than others and finished his apprenticeship in advance of others. In the past, people in the countryside were very fond of Guci;thus, Lu was happy to perform. It was very common that singing a long story would last for nearly ten days or even half a month. Afterwards, the “Cultural Revolution”like a rainstorm devastated both the folk art and the old man. During this period, Lu learned a bit of fortune telling for survival, then got married and had his own children. After the “Cultural Revolution”, nothing could dampen his enthusiasm for Guci; he switched to his former career. However, with the rise of television in the late 1990s, Guci was gradually fading. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Guci was on the verge of extinction. Nevertheless, Lu still treated it as his own child and never abandoned it. In recent years, the government and society has begun to pay attention to Guci and now regard it as an intangible cultural heritage. Even so, Lu has never been boastful. He still sings his Guci in a humble manner. He did not abandon Guci when it brought him sufferings, nor did he show arrogance when it brought him glory. He is very consistent in his love for Guci. We can say his life is marked with the imprint of Guci. It is this imprint on Lu Dingfeng that gave me and other team members a great shock.

Guci: Confronting Reality

Yongkang Guci is an important form of folk art in Jinhua region, Zhejiang Province. The unique form of performance, combined with melodious tunes, tells stories of justice and exhorts people to pursue goodness and develop good morality. Crispy drumbeats, bamboo clappers and the distinct Yongkang dialect bring out a great Chinese charm. Yongkang Guci has been experienced in many dynasties and become part of the memory of history and a precious treasure in culture as well. However, it faces the dilemma of inheritance as the artists like Lu Dingfeng are getting older and older.

With the progress of the times, there are various kinds of entertainment. Nowadays, the fast-paced life is depriving us of our time and patience to listen to artists singing Guci. These ancient cultures are fading and will not shine anymore. Some will vanish off the stage of history. The number of young people who are fond of Guci is on the decline. Feeling the lack of successors, the Yongkang department in charge of culture has taken effective actions, such as strengthening publicity, making it known to households, and inviting artists to give training classes in towns and local schools to consciously cultivate successors.

The river of history won't stop flowing for anyone, and we must keep pace with the times. I quite agree with Lu's opinion about Guci. We have every reason to protect it despite any difficulties. No one should bear the responsibility of Yongkang Guci's extinction in our generation. This exceptional experience makes me more mature. Faced with reality, my sadness is beyond words…It occurs to me that we have the responsibility to make more people aware of the existence of this folk art and the invisible but powerful strength of culture.

The Intangible Confronting the Tangible

“Intangible” in English means invisible and untouchable. By definition intangible culture refers to those invisible cultural forms, including such traditional customs and arts as art performances, social customs, festival celebrations and handicraft. The preservation and inheritance of intangible cultural heritage means a special Chinese lingering charm and a Chinese style of life to some extent, and this matters significantly in contemporary China when the pursuit of material culture is so prevalent.

Fortunately, we still have people who are guarding our culture like “the Catcher in the Rye”, and Lu, the person whom we have interviewed, is one of them. He is a representative inheritor of the intangible cultural heritage of Yongkang Guci at city level. He is using his life to perform this unique folk art and display the historical Chinese lingering charm. However, only one person's effort will not work to guard our culture, so we all must give our efforts to pick up our Chinese lingering charm, keep our Chinese style, and make intangible culture, traditions and ancient culture part of our material life, modern life and fashion culture. Guci can be part of our daily life. What a beautiful picture when either the young or the old people walk in a quiet garden with Yongkang Guci melodies in the morning or at dusk!

To make Guci part of our life, we still need to take more realistic questions into consideration. Yongkang Guci is performed in its local dialect. Though it increases its local characteristics, it also is a limitation for its wide spread. This feature would make it difficult for outsiders to understand what the aria is about, and it might even make them lose their patience when they try to enjoy it. I am wondering if it is possible to change its language into mandarin but still remain the original arias and tunes. If so, this market will expand, and we may even select some of its famous sections to be performed around the world after translating them into English. Yongkang Guci is a word-of-mouth folk art, so there are few scripts that exist now. And although some of the inheritors' works have been recorded, it will be difficult for people to learn it with the audios alone. It is also necessary to write the lines down on paper. We can adapt the lyrics while obeying its original characteristics and tips so as to be accepted by more people and to follow the pace of the times.

To make the inheritance of intangible cultural heritage an indispensable part of our fashionable and spiritual life, the Catcher in the Rye like Lu is much needed; what is more, we need to pour new elements into this intangible culture. There are no passers-by for this great cause; we all must have a share in its development: the inheritors, the government, society, scholars and us college students.